Six short months ago, the New Orleans Saints were considered legitimate Super Bowl contenders by the vast majority of NFL experts. I too wrote on this site in August that this would be the most talented roster the Saints have fielded since Sean Payton arrived in 2007, and New Orleans would be right up there with Green Bay and Seattle as the top teams in the NFC.

Back then, New Orleans was a team that had gone 11-5, 13-3, 11-5, and 13-3 in the last four seasons under Sean Payton, easily the most wins for any franchise during that span. The Saints had traveled to Philadelphia in the postseason and defeated one of the hottest teams in the league at the time, curing the road ails that had previously haunted this team. At Seattle the next week, the Saints gave the eventual Super Bowl Champion Seahawks all they could handle in a game that came down the final possession. Despite losing in the NFC Divisional Round of the playoffs, the tough road loss was quite the accomplishment for the Saints considering the manner in which the Seahawks decimated Peyton Manning’s Broncos and the greatest offense of all time 43-8 in Super Bowl XLVIII.

In short, the Saints were right there with the best the NFL had to offer. And what’s more?

The Saints were coming off what appeared to be an outstanding offseason. Free agency was kind to the Saints, as the team’s only noteworthy departures included a bunch of over-the-hill veterans, all of whom seemed easily replaceable. The defense had finally appeared to turn the corner in their first season under defensive coordinator Rob Ryan. The team broke the bank to bring in free safety Jairus Byrd, a bonafide playmaker who had led the NFL in interceptions the last three seasons. The Saints selected speedster Brandin Cooks in the first round of April’s draft, giving Brees a new toy to play with. General manager Mickey Loomis worked some more salary cap magic, squeezing out a mega contract for stud TE Jimmy Graham, locking up the unstoppable Brees-to-Graham combo for years to come.

The New Orleans Saints were on the cusp of greatness, and expectations throughout WHODAT Nation were sky-high. It was time for New Orleans to win another Super Bowl.

And then the season started…

Have you ever captured a spider and then proceeded to flush it down the toilet? It’s funny, because you can’t ever just leave the bathroom after you flush the spider. Even if it’s dead, you have to stay and watch it go all the down the toilet. At this point, you know the spider is pretty much hopeless, but you have to see this all the way through. The water starts spinning, and the spider circulates a few times. You keep watching, inevitably thinking that maybe there’s a chance the spider makes a miraculous escape. And then all of the sudden you realize that you’re kind of rooting for the poor thing, just to see what happens.

The 2014 New Orleans Saints were the spiders in that scene. Things got ugly real fast. But like a bad movie that never seems to end, this tragic Saints team somehow remained in the playoff hunt up until the season’s final week. The dumpster fire that was the NFC South division only masked the harsh reality that was the 2014 season. Yet in classic Saints’ fan fashion, we held on to the slightest glimmer of hope and opportunity each week, only for it to be washed away in the toilet that was our season.

So what the heck happened?

What was so different about this team?

To answer this question, I’m going to open this 8-part “State of the Franchise” series by explaining the only element that was NOT different or wrong about this team…

and that’s THIS GUY:

The biggest misconception around WHODAT Nation right now is that Brees is declining, and I think it’s a huge mistake to place even a small portion of blame for this disastrous season on his shoulders (or arm). Therefore, I’m going to do my best to dispel that notion in parts 1 and 2 of this series.

Granted, I can see how it’s easy to point the finger at Drew Brees. After all, he’s the quarterback. He’s our best and most valuable player. He’s our leader. And he’s our most expensive asset, taking up about 1/6 of our team’s salary cap… a payroll that 52 other players have to share. He’s also 36 years old, which is around the age when many quarterbacks see their skills deteriorate. Only two quarterbacks threw more interceptions than Brees, and quite a few of his 17 picks came in critical moments.

But just as the nicest sports cars are not going to drive smoothly with four worn-out, tires with minimal tread, even the most elite NFL quarterbacks are not going to thrive with underwhelming supporting casts.

In other words, I’m of the opinion that Drew Brees is NOT DECLINING, but rather he was forced to row a boat with feathered oars.

Brees’ lackluster supporting cast expanded further than his pass catchers on the outside though; the issues start up front in the trenches.

Poor pass protection was the biggest difference between the inconsistent 2014 offense and the prolific offenses we’ve seen in past seasons.

More than anything else, the unit’s struggles – particularly the inept play from the interior offensive line – hindered Brees’ production, and thus the offense’s efficiency.

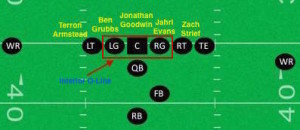

To be clear, the interior offensive line refers to the offensive guards and the center; these are the three interior players on the offensive line that line up between the left and right tackles. The Saints’ offensive line is composed of (from left to right) left tackle Terron Armstead, left guard Ben Grubbs, center Jonathan Goodwin, right guard Jahri Evans, and right tackle Zach Strief.

The New Orleans Saints have always placed a particular premium on their offensive guards. Financially speaking, that’s actually an understatement. In comparison to the rest of NFL teams, New Orleans pays a King’s ransom to ensure quality guard (for reasons that will be discussed later). For now, it’s essential to understand that no team even comes close to compensating its offensive guards more than New Orleans, making it crystal clear that OG is a position of priority which the Saints value extremely highly.

Few Saints fans may realize that guards Ben Grubbs ($11 million) and Jahri Evans ($9.1 million) had the second and third highest cap numbers on the team last season. Having two of the top-6 highest paid offensive guards in the NFL on same team is not only extremely rare, it’s ludicrous by NFL standards.

Accordingly, New Orleans spends more than every other team on the offensive guard position. Specifically in 2014, the Saints spent $20.5 million cap dollars on guards, which accounted for 15.51% of the team’s salary cap. By comparison, the team that spent the second highest amount on guards (ATL) spent $12.1M at the position, which accounted for 8.59%.

Simply put: the Saints spent almost twice the amount on their offensive guards than any other team in 2014! Take a moment to comprehend that fact.

And then contrast those figures with the Saints’ salary distribution on offensive tackles, a position that is universally deemed more important than guard and is therefore valued and compensated higher by almost every NFL team. The Saints spent $3.5M on the tackle position in 2014, which is merely 2.7% of team salary.

- Saints OTs = $3.5M collectively… 2.7% of team salary.

- Saints OGs = $20.5M collectively… 15.5% of team salary.

In short, the Saints’ guards are paid an unprecedented amount in NFL dollars to produce at a very high level.

At this point, if you’re currently thinking there must be a method to the team’s madness and are curious why the team values this position so highly, then we’re on the same page.

The answer to why the Saints treat this position completely different than every other team is based on the way Brees plays, and also the fact that good interior O-line play can mitigate his physical limitations.

Drew Brees has excellent pocket presence and textbook footwork; he is great at making subtle movements to sidestep oncoming rushers and never hesitates to step up into the pocket when he feels pressure from the outside. Accordingly, the Saints’ offensive tackles are simply taught to force pass rushers to the outside on pass plays because of Brees’ uncanny ability to step up into the pocket to buy the necessary time it takes to get the ball out to his targets. As a result, the Saints have not had to join the rest of the league in paying for high-quality offensive tackles to protect their quarterbacks.

However, as a result of Brees’ stepping up, it’s important to keep in mind that Brees is actually scooting closer to his interior linemen. This is when Brees’ height (or lack thereof) can present a problem, because the closer inside rushers push his guards back, the more difficult it is for Brees see over the tall offensive linemen in front of him. Moreover, because NFL defensive linemen are so massive, athletic, and long – and Brees is so short – it’s more challenging to arc the ball over or around their arms as they attempt to deflect or swat the pass down. This is why Brees is routinely among the annual leaders in passes batted down at the line of scrimmage.

Basically, if the interior offensive line does not get a good push on defensive tackles or blitzes from the inside, and Brees’ vision is drastically impaired, his throws won’t always be on the mark.

The situation is analogous to a shot blocker in basketball affecting the shot of an elite shooter; As dominant as Steph Curry may be, his shooting percentage is going to inevitably going to drop when he has a hand in his face as opposed to a clean look. Even the best shooters are more accurate when they have a clear line of vision to the basket.

In my eyes, Brees remains one of the most accurate passers in the NFL. Based on his second-to-none work ethic, it’s doubtful his he’s lost even the slightest touch of accuracy in one season. As a result, the relatively higher number of off-target throws last season can best be attributed to a greater number of plays where Brees was pressured or his vision was blocked.

The performance drop-off between the tackles is particularly a problem because Brees has always counted a clean pocket up the middle, where the shorter Brees loves to step into and find passing lanes.* He wasn’t afforded this chance to step up into a clean pocket as often in 2014, and even was, the passing lanes were smaller because the interior offensive line could not seem to get a good push on opposing defensive tackles.

In other words, the poor play from the interior offensive line hindered both his movement and his vision, leading to more “inaccurate” passes, which in turn disrupted the flow, consistency, and efficiency of what was previously a dominant offense.

The increased pressure from the inside also yielded more interceptions.

- Brees was under pressure on 9 of his 17 interceptions, the highest mark in league.

- It’s also likely no coincidence that 13 of Brees’ 17 interceptions came between the hash marks, meaning only four came on throws the outside.

Furthermore, according to ESPN splits for the 2014 season, Brees had a QB rating of 72.0 on middle direction passes, and recorded at least a QB rating of 95.0 in every other segment of the field (right side, left side, middle, left sideline, right sideline). This is a stark contrast from his 100.3 QB rating from passes directed toward the middle segment in 2013.

It’s certainly not a stretch to conclude Brees’ vision over the center of the field last season was impaired in such a way that differed greatly from two seasons ago.

Brees’ mastery in the pocket in terms of movement, feel, and timing all serve in mitigating any issues his height would present another quarterback his size. Alas, the reason there are so few 5’11 starting quarterbacks in this league is because they aren’t nearly as good as Brees. However, nothing is more beneficial than what the Saints have done over the years to combat his Kryptonite. That is, the front office has placed high priority on ensuring elite production from the interior O-line.

In 2014, however, this luxury wasn’t afforded to Brees, as the team’s guards and center did not play nearly well enough for the offense to be consistently effective as it has in years past.

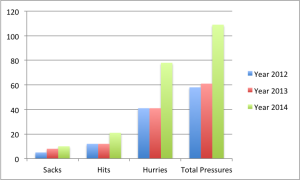

The following graph shows the total pressures allowed from the right guard, left guard and center positions in the past three seasons:

It’s easy to see that QB sacks, QB hits, and QB hurries were up across the board last season. But most alarmingly, the total pressures Drew Brees was forced to deal with practically doubled in 2014.

Per ProFootball Focus, RG Jahri Evans graded out terribly in pass protection; his -17.7 pass blocking grade ranked 77th of 78 qualifying offensive guards. The difference between 2014 and previous seasons was signficant. Prior to last season’s debacle, Evans had consistently been one of the league’s premier guards in all respects. Only Green Bay’s Josh Sitton had a higher combined grade than Evans’ +10.0 grade in 2013 and +11.9 grade in 2012.

The 34 quarterback hurries allowed by Evans was the worst mark for any interior offensive linemen in the NFL. He had noticeably bad games in week 12 vs. Baltimore and got manhandled by DT Gerald McCoy against Tampa Bay in week 5 (in his defense, McCoy is a monster). Embarrassingly, Evans gave up two of six sacks allowed on the season vs. the Falcons’ nonexistent pass rush in a backbreaking week 16 matchup when the Saints’ season was on the line.

It’s worth mentioning that Evans was reportedly limited by a lingering wrist injury the second half of the season that requires offseason surgery, but it’s fair to question if he is simply past his prime.

RG Jahri Evans’ pressures allowed in the past three seasons:

- 2012: 0 sacks, 4 hits, 15 hurries

- 2013: 2 sacks, 4 hits, 12 hurries

- 2014: 6 sacks, 7 hits, 34 hurries

Evans was not alone in his struggles. Fellow guard Ben Grubbs’ play also unexplainably dropped last season. While Grubbs has never played at an elite level like Evans, he has been a reliable, above average starter for the past five seasons. In 2014, he was not nearly as effective.

LG Ben Grubbs’ pressures allowed in the past three seasons:

- 2012: 3 sacks, 4 hits, 16 hurries

- 2013: 3 sacks, 5 hits, 20 hurries

- 2014: 1 sack, 6 hits, 27 hurries

Additionally, the center position was in flux all season long. The Saints couldn’t afford to pay Brian De La Puente, who followed former Saints O-Line coach Aaron Kromer to Chicago last offseason. BDLP had been a stable center for New Orleans for four seasons. The Saints chose to address the hole by signing Jonathan Goodwin, a 34-year-old veteran who had been released by the 49ers. Goodwin ended up battling a string of minor injuries, playing 12 games as a shell of his former self.

The raw, undeveloped Tim Lelito filled in for Goodwin while he was hurt. Although the causation to this correlation is likely minimal if any exists at all, it’s nevertheless interesting that the Saints went 5-0 in the five games Lelito played significant snaps in place of Goodwin. This could be an entirely unrelated coincidence, however, as Lelito is not yet developed into even an average starter (he has room to improve though).

Nevertheless, Goodwin nor Lelito could provide Brees the comfort and protection that BDLP could offer. And the instability and struggles at the center position – a position of added responsibility on the O-line in terms of signaling blocking assignments – disrupted the valuable continuity of the unit while making the guards’ jobs more difficult, as they often had to overcompensate for the center’s youth (be it Lelito) or struggles (be it Goodwin).

Total pressures from Saints Centers in the past three seasons:

- 2012: 2 sacks, 4 hits, 10 hurries (Brian De La Puente)

- 2013: 3 sacks, 3 hits, 9 hurries (Brian De La Puente)

- 2014: 3 sacks, 8 hits, 18 hurries (Jonathan Goodwin / Tim Lelito)

The unit’s struggles in the past two seasons, particularly their implosion last season, is not for poor health, nor does a lack of talent does not seem to be cause. The Saints’ starting five members along the offensive line have missed only 13 of a possible 160 games in the past two seasons. Additionally, the Saints have done an excellent job scouting for the unit over the years, uncovering gems like OT Terron Armstead and Zach Strief, OGs Jahri Evans, Carl Nicks, and center Brian De La Puente in the late rounds of the draft and even as undrafted agents.

The line’s recent hardships could be at least in part related to the departure of offensive line coach Aaron Kromer. How involved Kromer was in the scouting or draft decision-making process is unclear. What’s undeniable, however, is Kromer’s impact on their development. From rags to riches, Kromer brought out the best in these relatively unknown small school prospects, developing them into quality starters and even borderline superstars in this league… and in a short time frame, I’ll add.

Two seasons ago, Kromer left the Saints to take an offensive coordinator position with the Bears. While there are certainly other factors involved, it’s at least noteworthy that the unit’s play has regressed ever since Kromer’s departure.

The good news for the Saints is that their offensive tackle tandem is rock-solid.

RT Zach Strief has developed into a strong pass protector; he was particularly reliable in 2014, allowing only 3 sacks and 6 QB hits all season. Although he lacks superior athleticism, he has held his own more often than not in the last three seasons.

LT Terron Armstead possesses both good size and tremendous natural athleticism. Although the O-line as a whole was relatively healthy in 2014, it’s worth noting that the Saints’ offense was particularly ugly at times during the five games that Armstead sat out due to injury. Among the five contests Armstead missed were a blowout loss to Dallas, a 41-10 loss to Carolina, an embarrassing 30-14 loss to Atlanta, and a narrow 23-20 victory in the season finale over Tampa Bay, a team who not only finished 2-14, but arguably tanked in the second half of that contest to ensure the first overall pick in next year’s draft. Needless to elaborate more, things got ugly without Amstead.

Perhaps the main trouble with Armstead’s absence was less of a testament Armstead’s play and more about a lack of depth behind him; Bryce Harris was atrocious in pass protection when he filled in for Amstead. Harris allowed a whopping 7 QB hurries against Carolina and another seven against ATL when season on line.

The final minutes of a critical week 7 tilt with the Detroit Lions, as you may reluctantly recall, perfectly encompassed the offensive line’s struggles and the major impact it had on last season.

Here’s the situation:

- Following the BYE week, the 2-3 Saints had played their best game of the season thus far against the 4-2 Lions. Leading for the vast majority of the game, the Saints offense, up 6 points, desperately needed a first down or two to ice the game with a few minutes to play…

“For Brees, the final two drives against the Lions were a microcosm of the season. On 11 dropbacks over the final two drives, he was pressured eight times, including the interception with 3:20 to play that allowed the Lions to take the lead in the final minute.

Brees has to find a way not to make that mistake, but those things happen when you’re constantly feeling the heat.”**

The heat was unlike years past;

Drew Brees had almost a tenth of a second less to throw per play last season than he had for both 2013 and 2012.

Drew Brees Average Time to Throw:

- 2014: 2.63 seconds

- 2013: 2.72 seconds

- 2012: 2.73 seconds

A tenth of a second may not seem like much at first glance, but it’s A BIG DEAL. but consider the amount of plays where a tenth of a second makes the difference between executing and failing to execute a play. Indeed, football is a game of inches, and the body can move quite a few a bit in a tenth of a second. Moreover, considering Drew Brees dropped back to pass more than 700 times last season, the fact there was a full nine tenths of a second difference on average with that large of a sample size is telling.

Unfortunately, the Saints cannot use any strength of schedule argument as a possible excuse or defense of the team’s porous offensive line. Keep in mind that the majority of the Saints’ opponents in 2014 ranked near the bottom of the league in terms of sacks. While sacks are not truly indicative of a team’s pass rush, it’s safe to say that the pass rushes in Atlanta, Tampa Bay, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and Dallas – nine games against opponents which ranked 22nd or lower in sacks – presented more problems for the Saints than they should have.

The big picture is this: Drew Brees (age 36), Tom Brady (37) and Peyton Manning (38) are all elite pocket quarterbacks in the league, and they have carried their teams for a long time. They just can’t do it when they are pressured one out of every five snaps.**

Tom Brady and the Patriots’ O-line had the same problems up until week 5 in the regular season, when they finally found the right combination of players that patched their holes up front. Under less duress, Brady had more time to see the field and pick apart defenses the same way he used to when he was in his prime. The Patriots’ offense dominated thereafter, en route to their recent Super Bowl victory (and MVP for Brady).

Like Brady, Drew Brees is still playing at a VERY HIGH level (more on this later), but he needs a cleaner pocket so he can step up and find passing lanes. There’s a reason the Saints place such a high priority on quality interior offensive line play, and last season the unit as a whole was not good enough. The impact this had on the team’s ability to score and maintain possession of the ball was paramount for a franchise that thrives on offensive efficiency.

The road to the Super Bowl for the New Orleans Saints begins with clearing the path that obstructed Brees in 2014.

…

…

…

* = Mike Triplett, ESPN

** = Peter King, MMQB

Categories: NFL Feature Stories, The WHODAT GUIDE

Madden 20 Ratings – Saints Edition

Madden 20 Ratings – Saints Edition  Booger McFarland: Internet Meme to the MNF Booth

Booger McFarland: Internet Meme to the MNF Booth  2019 Saints Offensive Line Breakdown

2019 Saints Offensive Line Breakdown  Teddy Bridgewater: Staying or Leaving the Saints?

Teddy Bridgewater: Staying or Leaving the Saints?  Atlanta Falcons vs. New England Patriots: Super Bowl 51 Preview

Atlanta Falcons vs. New England Patriots: Super Bowl 51 Preview  LSU vs. Bama – Who Wins a Matchup Between the School’s Current NFL Players?

LSU vs. Bama – Who Wins a Matchup Between the School’s Current NFL Players?